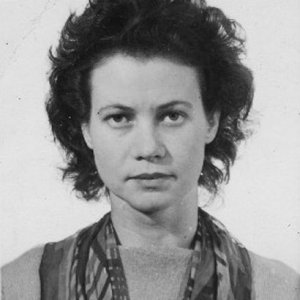

- SURNAME

Latour

- FORENAME

Phyllis Ada (Pippa)

- UNIT

F Section SOE

- RANK

Section Officer

- NUMBER

9909

- AWARD

Member of the British Empire, Croix de Guerre (Fr)

- PLACE

France 1944

- ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

parent unit Women's Auxiliary Air Force

born 8.4.1921 Durban,South Africa

joined WAAF November 1941 as 718483 ACW

original officer service number 8108

joined SOE 1.11.1943

codename Genevieve

Scientist Circuit (w/t op)

aka Paulette Janine Latour

married name Doyle postwar (divorced 1975)

awarded le Chevalier de l'Ordre National de la Legion d'Honneur (France) 2014

residing in New Zealand 2014

died 07.10.2023 (Aged 102)

Obituary:

Had it not been for the ingenuity of the Special Operations Executive’s technical branch and her own presence of mind, the 23-year-old Phyllis “Pippa” Latour, believed to have been the last surviving female agent in SOE’s F (France) Section, would probably not have lived to see VE Day.

She had parachuted into Normandy in the early hours of May 2, 1944, a few weeks before D-Day, to join the “Scientist” circuit of the Maquis, the French Resistance, as their wireless operator — or in SOE slang, “pianist”. The role of the Maquis was to gather intelligence on the Wehrmacht and targeting information for the Allied air forces, and then switch to active sabotage when the invasion began. Everything therefore relied on the wireless operator’s ability to send Morse code messages back to London and to remain undetected.

Knowing that the invasion was coming, but not precisely where or when, the Germans were on heightened alert. All civilian movement was potentially suspect and spot checks were frequent. Latour, her French sufficiently fluent and her looks youthful and Gallic enough to pass for une jeune fille normande, went about the Scientist area — some 40 square miles — by bicycle, passing as a soap-seller. One day, she and others were rounded up in a routine sweep and taken to the local gendarmerie for questioning. The SOE’s technical branch had miniaturised the tools of her trade, however: “I always carried knitting because my codes were on a piece of silk,” she recalled in an interview years later. “I had about 2,000 I could use. When I used a code I would just pinprick it to indicate it had gone. I wrapped the piece of silk around a knitting needle to insert it in a flat shoe lace which I used to tie my hair up.”

At the gendarmerie, “a female soldier made us take our clothes off to see if we were hiding anything. She was looking suspiciously at my hair so I just pulled my lace off and shook my head. That seemed to satisfy her. I tied my hair back up with the lace. It was a nerve-racking moment.”

It was one of several searches, but each time her childlike gaieté somehow got her through. Yet it had almost prevented her joining the SOE in the first place.

Phyllis Ada Latour was born in 1921 aboard ship in Durban, South Africa. Her father, Philippe, a French doctor, was on his way to the Belgian Congo. Her mother was English, but soon after reaching the Congo, with tribal war raging, her father sent them back to South Africa. He was killed not long afterwards.

When Latour was three her mother remarried. “My stepfather was well off, and a racing driver. The men would do circuits and they would often let their wives race against each other. When my mother drove, the choke stuck and she couldn’t control the car. She hit a barrier, the car burst into flames, and she died.”

Her father’s cousin became her guardian, and she went to live with his family in the Congo. “They were really the only parents I knew. When I was seven my ‘new’ mother went riding as she always did. The horse came back without her … When they found her she was dead.”

Latour was initially educated at home and then in Nairobi, Kenya, before in 1939 going to secretarial college in England. When war broke out she volunteered for the Women’s Royal Naval Service, who naturally enough given her secretarial skills put her to administrative work. Wanting something more active, in 1941 she transferred to the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) to train as a mechanic. There, her language skill was recognised and in 1943 she and a dozen others were sent for what was coyly known as special training: “It was unusual training — not what I expected, and very hard.”

Initially the SOE selectors were far from convinced she was the right material, an interim report describing her as “a naive, ingenuous girl with a love of excitement, full of a confident optimism in which judgment plays no part ... She is no more than a child in her gestures, behaviour and outlook and has no grasp of the realities of life. Quite unsuitable.” Or, as a female agent-turned-trainer remarked, “cheerful little scatterbrain … uncontrolled and stubborn”.

Eventually, though, “They told me they wanted me to become a member of the SOE. They said I could have three days to think about it. I told them I didn’t need three; I’d take the job now.”

Then began her real training. She already knew Morse code, but needed to speed up her key-work, and also to become handy with weapons. The SOE also employed a number of “old lags” to teach “tradecraft”. Latour increased her climbing ability thanks to a cat-burglar, and learnt to pick locks courtesy of a former peterman.

On April 30, 1944, the BBC broadcast the coded message “Le vin rouge est meilleur” (“Red wine is better”), notifying “Scientist” that Latour — codename “Genevieve” — would be landing. Two days after dropping into France she sent a message — the first of 135. By 1944, sending was the “pianist’s” most vulnerable moment. The high-frequency wirelesses needed to send on high power, with long antennae, and the Germans had developed an effective system of direction-finding (DF) by triangulation. “They were about an hour and a half behind me each time I transmitted. Each message might take me about half an hour so I didn’t have much time. It was an awful problem for me so I had to ask for one of the three DF near me to be taken out. They threw a grenade at it. A German woman and two small children died. I knew I was responsible for their deaths. It was a horrible feeling.”

Come the invasion, she had 17 wireless sets hidden in various farms, and was often living rough in woods and barns and always short of food. Her work only ended when the Americans overran the Scientist area. She returned to England in October, whereupon SOE proposed returning her to the WAAF, in which she now held the rank of Section Officer.

Latour protested. Her debrief report said “Tons of guts. Wants to go on with the work, provided it’s dangerous enough.” So she was re-briefed to drop behind the lines into Germany, but the mission was abandoned because of the rapid Allied advance after the crossing of the Rhine in March. She was instead discharged soon after VE Day, and appointed MBE (Military).

Subsequently she married Patrick Doyle, an Australian engineer, and lived in Kenya, Fiji and Australia. They divorced in the 1970s, and she brought up their four children in New Zealand on little money. In 2014, along with other Normandy veterans, she was appointed a chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur by the French government.

Latour remained loath to talk of her experiences, always conscious of the death she had brought to French civilians in consequence of the Allied bombing, and that 12 of her 38 fellow F Section female agents were executed by the Germans.

Source : https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/pippa-latour-obituary-sv9tc9np5

Last edited by a moderator: